Reading Europe with Muslim Eyes (REME)

This piece explores the philosophical underpinnings of REME and affirms the fundamental role history plays in tempering understandings of our current moment.

November 29, 2025

Author: Farah El-Sharif

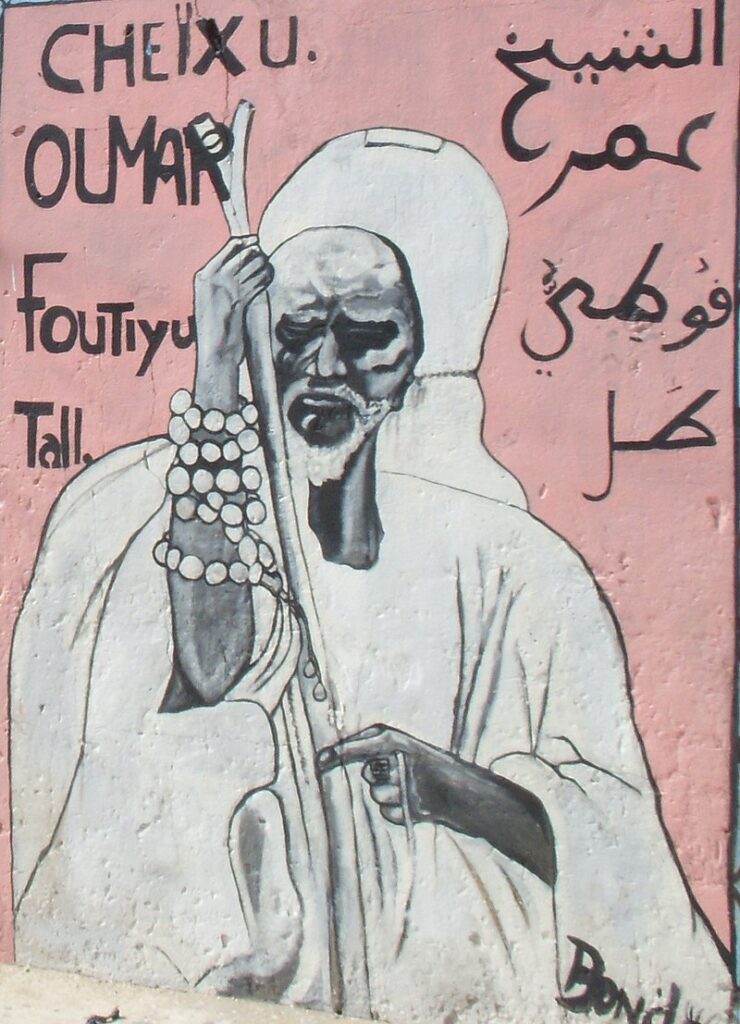

In 1995, Islamic Africa specialist John Hunwick lamented that Kitāb al- Rimāḥ “lies unstudied by Africanists and Islamicists like a hard lump in the stomach, massive and undigested.” Enabled by the works of countless scholars who have made enormous inroads into the field of Islamic scholarship in West Africa today, my PhD dissertation sought to tackle this leviathan-sized nineteenth century West African text by Ḥajj ʿUmar Futi Tāl (d.1864).

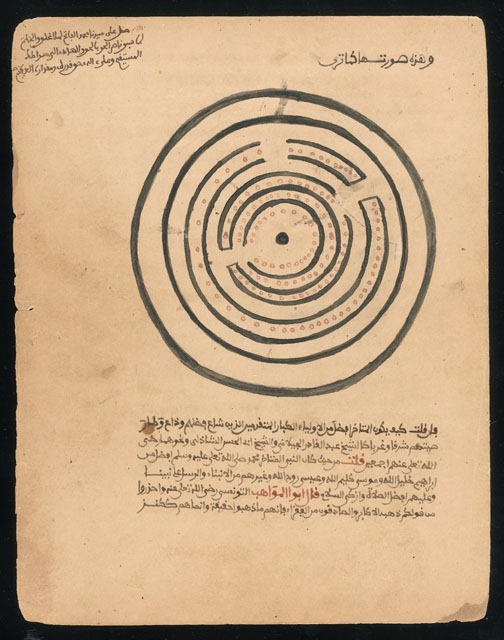

My personal connection with the Rimāḥ can be described as serendipitous: rummaging through the famed downtown Dandis bookstore in my native Amman in 2010, the golden embossed printed version seemed to jump out of an obscure shelf and into my hands. I haven’t been able to put it down ever since! The first edition I owned was, as it usually is, printed on the margins of the Tijaniyya’s primary text, the Jawāhir al-Maʿānī transcribed by ʿAlī Harazim Barrada, Shaykh Aḥmad Tijānī’s (d.1815) most ardent disciple. The printed Rimāḥ is normally based on the 1927 Tunis edition, but it is, as is the case with print editions, full of mistakes, which is why I relied on early manuscript editions for my research. This is also why a series of extensive editing processes are currently underway in Cairo and Rabat. Because it is usually printed on the margins or as an appendix to the Jawāhir, the Rimāḥ has–quite literally–been marginalized for so long by Islamicists and Africanists alike.

The Rimāḥ is comprised of 55 chapters and is a Sufi compendium from the impressive corpus of West African literature in Arabic. The category of “Sufi texts” itself must be used with a disclaimer however, as the term risks conjuring unexamined tropes about the work of scholars with strong commitments to Sufism. One false association tied to “Sufi” works is that they are “nonrational” (i.e., esoteric) and therefore un-scholastic. This perception can lead to the emergence of blind spots when it comes to the study of Sufism and Islamic mysticism. Another blind spot in this field is the demarcation between African and Islamic studies: luckily, recent scholarship such as that of Rudiger Seesemann, Ousmane Kane, Rudolph Ware, and Zachary Wright combats this false divide. My approach to the text from the onset was to appreciate its intellectual and scholarly contributions to Islamic intellectual history, casting aside pre-conceived notions of what a Sufi text “should” read like.

Hailed as Bilād al-Sudān’s (sub-Saharan Africa) most widely disseminated text in its time, the Rimāḥ is intellectually significant because of its elaborate articulation of khatmiyya (the sealing or completion of Sufi sainthood), standing as the single most cohesive, cogent, and comprehensive compendium for the ṭarīqa Muḥammadiyya (the Prophetic path) in West Africa. This articulation of khatmiyya is what makes the Tijaniyya unique: it saw itself as a final ṭarīqa, just as the Prophet was the final Messenger, and this finality gave Tāl a sense of bolstered authority as the khalīfa (inheritor) of the seal of saints in West Africa.

It took Tāl eight years to pen the text, which means he was writing and adding to it over the course of his most enriching years as a pilgrim, a khalīfa, a scholar, and a leader. It was his camaraderie with Muḥammad Bello–son of the legendary leader ʿUthmān Dan Fodio–during his tenure in the Sokoto Caliphate that spurred the Rimāḥ’s writing, which he completed less than a decade later in Jegunko in modern day Mali in 1845, where he finally established his community and became its authoritative leader.

In my dissertation, I focus on the following key themes: the Rimāḥ’s borderline anti-taqlīd position, its exposition of the tarīqa Muḥammadiyya methodology and its criticism of “excesses” among Sufis and non-Sufis alike. Far from being a docile Sufi, Tāl was hailed as the ultimate “anti-Sultan”, who was deeply critical of authority figures and called out what he saw as “abuses” of religious and political power. Tāl seemed to invite conflict with his ineffable unapologetic disposition towards justice, and his blazing commitment to reform by way of spreading knowledge. Though he was solely focused on teaching, writing and helping people along the way for over 50 years of his life, this garnered the jealousy, negative attention (and oftentimes, racism) of African and Arab rulers and French colonial administrators who immediately saw his growing influence with apprehension and suspicion, which eventually thrust him into the throws of armed resistance in the last decade of his life before his eventual disappearance in a cave in modern day Mali.

A key chapter in my dissertation, entitled “Interauthors in the Dhawq-sphere: The influence of 15th and 16th century Egyptian scholars” discusses why it is significant that half of the copious quotes of the Rimāḥ come from ‘Abd al-Wahhāb al-Shaʿrānī (d.1565). Their interauthorial relationship depended on Tāl’s understanding of a metaphysical space that can only be known by direct experience– a shared gnostical “taste”-and not merely rationalized or thought of.

In undergoing a serious excavation of the intellectual sources of the Rimāḥ, few studies have scratched the surface of Tāl’s inspiration and influences. The number of direct quotations in the text and the breadth of citations from hundreds of sources, from Ḥasan al-Baṣrī (d.728) to Ibn ʿArabī (d.1240), to al-Dabbāgh (d.1719) and others are so numerous in the Rimāḥ that Bernd Radtke devoted an entire paper solely towards a study that outlines the sources of the text. But citing al-Shaʿrānī, I argue, invigorates and refurbishes Shaʿrānī’s and (other Sufi scholars’) overall project in a manner which attempts to breathe new life into their works as co-authors of the Tijani doctrine.

Shaʿrānī and Tāl’s shared emphasis on the ṭarīqa Muḥammadiyya, their critiques of Sufi “excesses”, their gnosis-guided approach to sharīʿa, their mutual “anti-sultan” political orientation and the messianic, end-times backdrop for their doctrines are the key themes that bind their respective projects. In addition, Shaʿrānī is credited for having “popularized” the thought of Ibn ʿArabī which, defies faulty perceptions that “neo-Sufism” and its precursors were marked by a rejection of Akbarian thought. Indeed, Patrick J. Ryan is correct when he credits the Tijani order for simplifying “much of this esoteric thought of Ibn ʿArabī, making it available to ordinary Muslims in concrete devotional practices.” ((Patrick J. Ryan, “The Mystical Theology of Tijānī Sufism and Its Social Significance in West Africa,” Journal of Religion in Africa 30, no. 2 (2000): 209, https://doi.org/10.2307/1581801.))

More importantly, because of the Rimāḥ’s emphasis on the doctrine of khatm al-wilāya al-Muḥammadiyya (“the Seal of Muḥammadan Sainthood”), the Tijaniyya quickly gained considerable ground in the landscape of Islam in West Africa. My dissertation posits that Tāl’s project is one of the most vividly articulated, coherent claims to the Sealing of Sainthood in Islamic intellectual history and led to the creation of Sufi orders in West Africa, as we know them today. Perhaps it is the paradigm of self-actualization through the experiential knowledge of God, what for centuries has been known by scholars as taḥqīq (realization), and not taqlīd or even tajdīd that can aid us in understanding the Sufi renaissance in 19th century West Africa, which reverberates strongly to this day in West and North Africa, and in the Western diaspora.

Farah El-Sharif is a scholar of contemporary Islam and Islamic intellectual history. She received her PhD from Harvard University, where her dissertation was on the most widely disseminated Islamic text in 19th century West Africa. Farah’s academic interests lie in Islamic scholarship from Africa and the Middle East, modern thought, epistemology, the nation state and the intersection of Islamic law and Sufism. She received her Master’s degrees in Islamic Studies from the Graduate Theological Union in Berkeley and Harvard University’s Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations. She completed her undergraduate degree at Georgetown University’s School of Foreign Service and has done research in Jordan, Egypt, Morocco and Senegal.

Notes / References

| ↑1 | Patrick J. Ryan, “The Mystical Theology of Tijānī Sufism and Its Social Significance in West Africa,” Journal of Religion in Africa 30, no. 2 (2000): 209, https://doi.org/10.2307/1581801. |