Reading Europe with Muslim Eyes (REME)

This piece explores the philosophical underpinnings of REME and affirms the fundamental role history plays in tempering understandings of our current moment.

November 29, 2025

Author: Adil Mawani

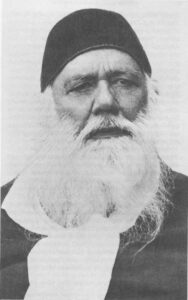

One hundred and fifty years ago the social reformer, Sir Sayyid Aḥmad Ḵẖān (d. 1898), had an opportunity to travel to Great Britain. I have often tried to imagine what he would have thought of the chance to visit the heart of the British Empire. A glimpse into his experience is possible since the Delhi native carefully documented his journey. In his time, travel writing had become popular for its ability to entertain, inform, and educate. As accounts of travel to Mecca, Karbala, and other places of pilgrimage, some works were even thought to confer religious benefits. After a brief discussion of the development of travel literature, I explore Sir Sayyid’s text, the circumstances in which he composed it, and the controversies that brought its publication to an abrupt stop.

What characteristics are common to the early travel narratives of South Asia? A colonial era falsehood was that Indians were a confined people, rarely travelling beyond their localities. In reality, for inhabitants of the subcontinent, travel within India and beyond its borders was an undeniable necessity. The misconception may have been propped up by the truth that lengthy travel in South Asia was arduous before developments in travel infrastructure, such as train networks and places where travellers could safely lodge. This may explain the first characteristic common to travel writing before the 1800s where travel was routinely presented negatively as uncomfortable, largely devoid of benefit, and even dangerous to one’s life. The second common characteristic was that writers left out the experience of the expedition itself. The focus, instead, was entirely on the time spent at the destination or the location abroad (Majchrowicz 2015, 4).

Although the printing press was brought to the subcontinent by Portuguese missionaries in the middle of the 16th century, technology for the scripts used in India was not adapted until the late 1700s. Commercial printing in North India then became active in the late 1830s with readers able to find texts in categories such as biography, medicine, law, and others (Stark 2009, 29). Amongst these, travel writing quickly became a highly sought after genre. In fact, the first Urdu travelogue preceded the Urdu novel by about three decades (Majchrowicz 2015, 29). Ironically, Urdu travel literature had become popular in the first half of the 19th century on the basis of translations since, up to that point, no original travel writing had been composed in Urdu.

The explanation for the popularity of the category has to do with the mandate the colonial authority had given to itself to broaden education in India. As a consequence, literary categories did not reflect the Indian readership but followed the preferences of British civil servants who had designed them. Colonial administrators regarded travel writing as beneficial for their potential to motivate Indians to travel more and to help rid them of their “superstitious” beliefs. With the realization that Indian commercial presses were not issuing books in this category, measures were taken to fill this gap. As a result, the first Urdu travelogue to be published was printed in London in 1827, written by an English officer stationed in Bangalore. The book was an Urdu translation of the Persian original by Iʿtiṣāmudīn, a Mug̲ẖal diplomat who had made the journey from Bengal to Europe in 1766. Travel literature published in the decade that followed was also primarily of Urdu translations of texts composed by European adventurers documenting their voyages to the colonies. An example is Mungo Park’s 1842 work, Travels to the Interior of Africa (Majchrowicz 2015, 52). There is little chance, then, that readers in India were poring over classical works such as al-Riḥlah (“The Travels”) by the 14th century Moroccan, Ibn Bat̤ūt̤ah, or the 11th century Persian-language Safarnāmah in which Nāṣir Ḵẖusrav recounted his seven-year journey.

All the cases mentioned so far involve male authorship. Is there evidence of women Urdu writers documenting their travel experiences? One challenge in finding female-authored travel writing is that they are mostly confined to women’s journals, a periodical form not well preserved in the archives. We should also keep in mind that even at the turn of the twentieth century women’s literacy was terribly low in South Asia, restricting the quantity of travel accounts produced by women. One surviving example is that of Atiya Fyzee (d. 1967) who in 1906, just shy of age thirty, travelled from Bombay to Britain on a two-year scholarship. Although an illness kept her from completing the program, she documented her time in England in the form of letters she penned to Zehra and Nasli, her sisters at home (Lambert-Hurley 2010, 1). As the letters arrived, they were published serially in the Urdu women’s journal, Tahẕīb un-Niswān (“Women’s Culture”). In 1921, these were compiled and published as a monograph titled Zamānah-yi Taḥṣīl (“A Time of Education”). The publication of travel accounts, thus, continued to increase in the second half of the 1800s. In fact, by the 1870s, the time when Sir Sayyid composed his work, the trend of translations outnumbering original Urdu works had become reversed.

Sir Sayyid’s journey began on April 1, 1869 and was routed from Benares to Bombay by a combination of bullock cart and railway, then by steamship and train to Aden, Alexandria, Marseilles, Paris, Dover, and finally to London. Just over a month of travel was required to complete the trip. By the end of April, Sir Sayyid’s posts from London began appearing in the Aligarh Institute Gazette, and were regularly published in serialized form. His work displayed substantial changes in the two traits common to early South Asian travel writing. First, details about the journey itself were central to the composition. Sir Sayyid included plenty of factual details, for example, by documenting the dimensions of the steamships on which he travelled, the kinds of technology used to guide the vessels, as well as the types of bathroom and bathing facilities on board. He also described interactions with the people he encountered. These descriptions reflected a new communal awareness that, historians explain, had intensified in India due to British approaches to administration. Therefore, Sir Sayyid often mentioned the regional and religious identities of the people he met, jotting down that someone was Parsi, Marwari, Bengali, and so on. He usually followed this with a comparison to the Delhi Muslim community with which he was familiar. This type of delineation is absent, however, in his observations in England where he mostly expressed admiration for the comparatively high level of literacy even amongst the working class. Unexpected from a travel account of this time, Sir Sayyid provided a review of the company that had arranged his sea travels by rating the quality of the food onboard and the lodgings. He wrote that while other passengers had been dissatisfied with some meals, he had not registered any significant complaints.

The second change was that instead of disparaging the experience of his journey, Sir Sayyid encouraged his readers to also travel. Although he offered favourable descriptions, for instance of his first impressions of European cities, he by no means produced an idealized picture. Therefore, during sojourns in Marseille and Paris he expressed awe at the cleanliness of the roads, the luxurious storefront windows, and the gas lamps illuminating the city at night. However, this was balanced by forthright descriptions, such as of the aches resulting from bullock cart travel, or the intense motion sickness that had overcome passengers during rough portions of the sea journey.

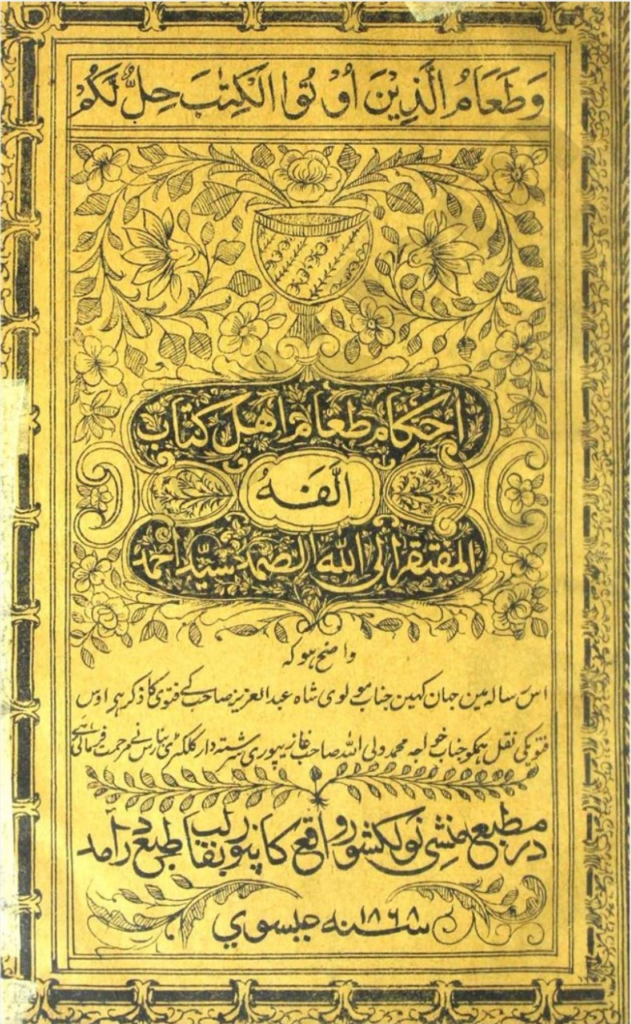

Despite Sir Sayyid’s efforts, a positive attitude to traveling abroad had not caught on in India. This is evident in the adverse reactions of Indian readers that led to the termination of his travelogue’s publication in August of 1869. Some had come to regard the trip itself as a transgression and newspaper columns accused Sir Sayyid of kufr (“apostacy”). This was rooted in objections to Sir Sayyid’s descriptions of consuming meals with Europeans, which included eating non-ẕabīḥah meat (slaughter complying with Islamic legal codes). We may detect the conspiratorial tone in other reports circulating in India claiming that after converting to Christianity in London, Sir Sayyid was now on a quest to take all Indians down that path (Pānīpatī 1961/2009, 29). The journey had turned Sir Sayyid into a harbinger of both the dangers and the possibilities of the new era where Muslims would experience life under a British authority. Fearful and conservative segments therefore saw an agenda in the travelogue, initiated by Sir Sayyid or others, to accelerate reconciliation between Indian Muslims and the English.Sir Sayyid was unlikely to have been able to perceive these issues. His enthusiasm to share what he had seen simply provoked resentment from his readers.

In November, publication of Sir Sayyid’s travel writings resumed. He wrote at length to reassure prospective Indian travellers by including practical advice on how both Hindus and Muslims could travel without compromising their religious beliefs. In another piece, he explained that what he had seen over his six-month stay compelled him to share observations in order to stimulate improvements at home. The rhetoric that the author employed, perhaps purposefully to shake up his readers, only inflamed them further. In one column, he described even the most accomplished and learned Indian as little more than a grime-encrusted animal when compared to the cultured and refined Englishman. Although these words were harsh, he concluded this column by assuring Indians that with the right systems of education they, too, could achieve similar levels of development. This suggests that he had adopted his tone strategically to motivate his fellow nationals. This time the publications were not suspended but by March Sir Sayyid was compelled to publish a column titled “An Apology from the offender, Sayyid Ahmad,” in which he conveyed his regrets.

Sir Sayyid completed the manuscript of his travelogue on March 11, 1870 naming it Safar-Nāmah, Musāfirān-i Landan” (“An Account of the London Travellers”). The book was not published, however, until 1961. In addition to the journal entries, the editor included some personal letters that the author had written to a close friend. These materials give a very different view of the experience abroad. Examples include Sir Sayyid’s elation upon discovery of stacks of Islamic Studies texts at the British Museum library, his having to contend from overseas with the passing of his only daughter, and his anxiety produced by extreme financial difficulties that troubled him for the duration of his trip.

His biographer, Alt̤āf Ḥusain Ḥālī, later clarified that Sir Sayyid was focused on the social improvement of Indians. His appeals and apologies may not have reached all the people that he had had in mind. However, the work that he undertook upon his return to India demonstrated the sincerity of his intentions. It is interesting to reflect upon how his account, despite the expanse of time, resonates with the experience of travel today. I have in mind the author’s excitement, worries over his dietary practices, and the internal conflict he felt regarding the conditions at home and the situation he was witnessing abroad.

Adil Mawani is a PhD candidate at the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto. His primary interests are in religion in early modern South Asia, and South Asian expressions of Islam in the form of religious literature. His doctoral research is on the Sira tradition (sacred biography of Prophet Muhammad). In his dissertation project he focuses on the mid- and late-nineteenth century Urdu writings by Sir Sayyid Ahmad Khan on Muhammad, and Shibli Numani’s early twentieth century Urdu Sira text. At some point he aims to revisit his MA research on the encoding of religion in Salman Rushdie’s novel The Satanic Verses.

Aḥmad K̲h̲ān, Sayyid. (2009) Safarnāmah, Musāfirān-i Landan. Edited by Muḥammad Isma’īl Pānīpatī, Aligarh Muslim University. (Original work published in 1961)

Ḥālī, K̲h̲vājah Alt̤āf Ḥusain. (2000), Ḥayāt-i Jāved. Arsalān Buks. (Original work published in 1901)

Lambert-Hurley, Siobhan. Atiya’s Journeys: A Muslim Woman from Colonial Bombay to Edwardian Britain. New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Majchrowicz, Daniel J. Travel, Travel Writing and the “Means to Victory” in Modern South Asia. 2015. Harvard U, PhD dissertation.

Pānīpatī, Muḥammad Isma’īl. (2009) “Introductory Essay.” in Safarnāmah, Musāfirān-i Landan, Aligarh Muslim University. (Original work published in 1961)

Stark, Ulrike. An Empire of Books: The Naval Kishore Press and the Diffusion of the Printed Word in Colonial India. Permanent Black, 2009.